Upgrading to CE Level 2 armor isn’t the only path to better protection; the real key is minimizing transmitted force through proper system integration.

- Armor that shifts or rotates on impact offers zero protection, regardless of its certification.

- Modern flexible armor can meet high protection standards without the stiffness of traditional pads.

Recommendation: Prioritize a snug, articulated fit over a higher CE rating alone. An armor that stays in place is the one that will save you.

For the daily commuter, the choice in motorcycle gear often feels like a compromise between robust protection and all-day comfort. The market is flooded with labels like “CE Level 1” and “CE Level 2,” leading many to believe that the higher number is always the superior choice. This creates a dilemma for riders who want maximum safety but detest the stiff, bulky feel of heavy-duty armor on their way to the office. The common advice is to simply buy the highest-rated gear, but this oversimplifies a complex and critical decision.

But what if the debate isn’t about Level 1 versus Level 2? What if the true measure of protection lies not in a single label, but in the engineering of the entire protective system? The core of effective safety is found in the physics of force transmission and energy dissipation. A high-level certification means nothing if the armor isn’t positioned correctly at the moment of impact. This analysis moves beyond marketing tags to focus on the data that matters: kilonewtons of transmitted force, material science, and the critical role of fit.

This guide will deconstruct the components of a truly effective protective setup. We will analyze the fundamental differences in impact absorption, compare the abrasion resistance of leading fabrics, and demystify advanced technologies like airbags. By focusing on the principles of system integration, you will learn how to build a gear collection that provides superior, data-backed protection without sacrificing the comfort required for your daily commute.

This article provides a detailed breakdown of the critical factors in motorcycle gear selection, from impact ratings to material science. The following summary outlines the key areas we will analyze to help you make more informed decisions about your personal protective equipment.

Summary: A Pragmatic Guide to Motorcycle Gear Analysis

- Why the Foam Pad in Your Jacket Isn’t Real Back Protection?

- Kevlar vs Cordura: Which Fabric Survives a 60mph Slide Without Bursting?

- Mechanical vs Electronic Airbag Vests: Which Deployment System is More Reliable?

- Why Knee Armor That Rotates Is Useless in a Crash?

- The Forgotten Impact Zone: Why You Should Never Remove Hip Armor for Comfort?

- Polycarbonate vs Composite Shells: Which Absorbs Energy Better in a Crash?

- Amortizing Gear: How to Calculate the Daily Cost of a $1,000 Suit?

- The Layering System: How to Stay Warm at 40°F Without Bulky Electric Gear?

Why the Foam Pad in Your Jacket Isn’t Real Back Protection?

The thin foam insert found in many motorcycle jackets provides a sense of security, but from a force-transmission perspective, it offers negligible protection. The critical differentiator between this foam and certified armor is its ability to manage impact energy. The EN 1621-2 standard governs back protectors, defining specific performance thresholds measured in kilonewtons (kN) of transmitted force. A lower kN value signifies better protection, as less force reaches the rider’s body.

Certified armor is engineered to pass rigorous testing. According to these testing standards, CE Level 2 armor must transmit an average of less than 9 kN, while Level 1 allows up to 18 kN. In contrast, a non-certified foam pad can transmit well over 40 kN of force from the same impact. This means a CE Level 1 protector is at least twice as effective as a basic foam pad, and a Level 2 protector reduces transmitted forces by over 75% in comparison. The difference is not incremental; it’s a fundamental shift in safety capability. Modern material science has also produced flexible, non-Newtonian materials that meet these standards without the rigid feel of older armor, directly addressing the commuter’s need for comfort.

The following table breaks down the performance differences based on established certification data.

| Armor Type | CE Level 1 Force Limit | CE Level 2 Force Limit | Typical Foam Pad |

|---|---|---|---|

| Back Protector | 18 kN average | 9 kN average | Not certified |

| Single Impact Max | 24 kN | 15 kN | Can exceed 40 kN |

| Multi-Impact Capability | Maintains protection | Maintains protection | Degrades after first impact |

Kevlar vs Cordura: Which Fabric Survives a 60mph Slide Without Bursting?

While impact protectors manage force from a single point, the outer shell of a garment is responsible for resisting abrasion during a slide. A fabric failure, or “burst,” exposes the rider’s skin and renders any underlying armor useless. The two most recognized names in this space are Cordura (a brand of nylon) and Kevlar (an aramid fiber). However, comparing them directly is complex; the material itself is only part of the equation. Weave, fabric density (measured in denier), and coatings all play a critical role in abrasion resistance.

Cordura, particularly in densities of 500D to 1000D, is a workhorse material known for its excellent durability and resistance to tearing and abrasion. Kevlar is often used as a reinforcement layer in high-impact zones like the seat, elbows, and knees due to its exceptional heat and cut resistance. It is less stable under UV light and is therefore typically used as an inner liner. Industry testing confirms that many materials, including 600D Cordura, consistently meet the slide time requirements for CE certification under standards like EN 17092.

The choice is not simply Kevlar vs. Cordura, but rather a well-constructed garment that uses these materials strategically. The microscopic view below reveals the difference in weave structure, which is fundamental to how these fabrics handle the stress of a slide.

As the image illustrates, the interlocking fibers create a shield designed to withstand intense friction. A tighter, more robust weave will hold together longer, buying precious seconds for the rider to slow down. Therefore, a garment’s overall construction and certification level are more telling than the presence of a single brand-name fabric.

Mechanical vs Electronic Airbag Vests: Which Deployment System is More Reliable?

Airbag vests represent the pinnacle of impact protection technology, but their effectiveness hinges on one critical factor: deployment reliability. The market is primarily divided into two systems: mechanical tether systems and sophisticated electronic systems. Mechanical vests use a physical lanyard connecting the rider to the motorcycle. When the rider separates from the bike with sufficient force, the tether pulls a key, puncturing a CO2 canister and inflating the vest. This system is simple, requires no charging, and is proven to be highly reliable in scenarios where the rider is thrown from the bike.

Electronic systems use a suite of sensors (accelerometers, gyroscopes) and complex algorithms to detect a crash scenario. They can deploy faster than mechanical systems and can activate in situations where a tether might not, such as a low-side crash where the rider doesn’t fully separate from the bike. However, they require regular charging and rely on software to make a split-second decision. Certification standards for airbags, like EN1621-4, are designed to test for specific impact scenarios. Data shows that vests certified under this standard offer robust protection, though some brands also pursue additional protocols for different impact types. Ultimately, the choice depends on the rider’s tolerance for system complexity and maintenance.

Regardless of the system, verifying its certification is non-negotiable. As Matthew Dawson of Forcefield Body Armour states, this is the only way to ensure a baseline level of tested safety. In his own words:

Anything that carries the correct labeling must be tested and certified. Any brand with the correct marking and labeling should be able to produce that certification on request

– Matthew Dawson, Forcefield Body Armour

Why Knee Armor That Rotates Is Useless in a Crash?

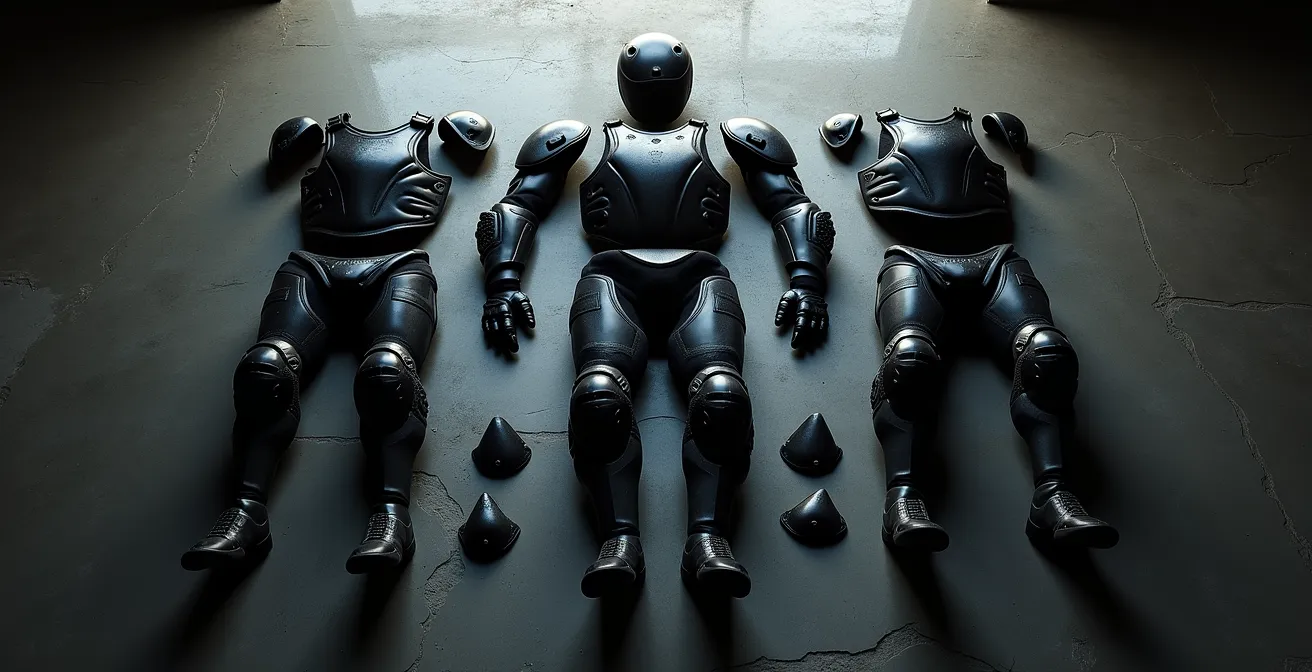

A CE Level 2 knee protector offers superior force absorption on paper, but if it’s not covering your kneecap during an impact, its rating is irrelevant. This is the single biggest failure point in motorcycle pants: armor that rotates or migrates away from the joint. For a commuter who is constantly moving, sitting, and walking, a secure fit is paramount. The armor must be held in place by either a well-designed internal pocket system or, ideally, an adjustable harness within the pants.

The problem is exacerbated by loose-fitting or “casual-style” riding jeans that lack the structure to keep protectors in position. During the violent tumbling of a crash, centrifugal force will pull any loose object away from the body. If the armor can shift with a simple leg twist while you’re standing, it will offer zero protection when you actually need it. To ensure proper coverage, protection experts often recommend Type B armor, which offers a more extensive coverage area than the smaller Type A, providing a larger margin for error. However, even Type B armor is ineffective if the garment allows it to move freely.

A properly integrated protector, as shown, should conform to the joint and remain in place through a full range of motion. The best way to check this is with a simple physical test before you ever ride.

Your Action Plan: The Kneel and Twist Test for Armor Fit

- Put on your riding pants with the knee armor installed and properly positioned.

- Get into a deep kneeling position on one knee, simulating contact with the ground.

- While kneeling, twist your lower leg from side to side and observe if the armor shifts off your kneecap.

- Stand up and perform a deep squat, checking for any significant migration of the armor.

- If the armor moves more than a trivial amount in either test, the fit is inadequate. Consider pants with a better internal harness or switching to larger Type B armor.

The Forgotten Impact Zone: Why You Should Never Remove Hip Armor for Comfort?

While knees and elbows are obvious impact points, the hips are one of the most frequently injured areas in a motorcycle crash, yet hip armor is the first thing many riders remove for comfort or a slimmer profile. This is a critical mistake. An impact to the side of the pelvis can be debilitating, and the thin, flexible hip protectors included with most quality riding pants are remarkably effective at mitigating this specific risk. They are a classic example of a low-profile solution providing a high degree of targeted safety.

The argument for removal often stems from a misunderstanding of the armor’s purpose. It’s not designed to prevent all injury from a catastrophic impact, but to absorb and spread the force of a common slide or fall, turning a potential fracture into severe bruising. The technology in modern hip protectors, often using the same flexible, energy-absorbing materials as knee armor, makes them barely noticeable when riding or walking. They conform to the body and do not create the uncomfortable pressure points that bulkier armor can.

The data on their effectiveness is clear. Multiple studies and accident analyses have been conducted, and the consensus is that wearing certified protectors dramatically improves outcomes. In fact, research demonstrates a 60-70% risk reduction for severe injuries when impact protectors are worn in the corresponding body zones. Removing them for a marginal gain in comfort is a poor trade-off from a risk analysis perspective. The protection they offer in one of the most vulnerable and complex areas of the body is too significant to ignore.

Polycarbonate vs Composite Shells: Which Absorbs Energy Better in a Crash?

A helmet’s primary job is to manage the energy of an impact to reduce the forces transmitted to the brain. This is accomplished by the combination of its outer shell and the inner Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) liner. The shell has two functions: to prevent penetration from sharp objects and to begin the process of energy dissipation by spreading the impact force over a wider area. The two dominant shell materials, polycarbonate and composite (fiberglass, carbon fiber, Kevlar), achieve this through different philosophies.

A polycarbonate shell is designed to flex and dent upon impact. This deformation is a form of energy absorption. It’s an effective, one-time-use strategy that allows manufacturers to produce very safe helmets at an accessible price point. A composite shell, by contrast, is more rigid. It manages energy by delaminating and fracturing, spreading the force across its woven fiber structure. This can sometimes offer better resistance to multiple impacts in a single crash scenario, though any helmet that sustains a significant impact should always be replaced.

Ultimately, the shell material is only half the story. The EPS liner is the main component responsible for absorbing the impact by crushing. The density of this liner is tuned to work in concert with the shell’s properties.

Case Study: Helmet Shell Energy Management Philosophy

An analysis of helmet safety standards reveals two primary approaches to energy absorption. Polycarbonate helmets utilize a ‘denting’ method, which is highly effective for single, significant impacts and is cost-efficient. In contrast, composite shells employ a ‘flex and delaminate’ strategy. This approach spreads impact forces across the shell’s structure, potentially offering better performance in complex crashes with multiple contact points. However, experts emphasize that the density and design of the internal EPS liner play an equally critical role in overall energy absorption, regardless of the outer shell material.

Amortizing Gear: How to Calculate the Daily Cost of a $1,000 Suit?

The high upfront cost of premium motorcycle gear is a significant barrier for many riders. A $1,000 riding suit can seem like an extravagance, but this perspective changes when the cost is amortized over the equipment’s useful lifespan. Viewing protective gear as a long-term investment in personal safety, rather than a one-time expense, provides a more accurate financial picture. A high-quality suit isn’t just fabric and armor; it’s a durable good with a multi-year service life.

To calculate the true daily cost, you must consider the initial purchase price, the expected lifespan of the components, and any maintenance or replacement costs. A quality textile shell might last 5-7 years, but the impact protectors within it have a recommended lifespan of around 5 years and must be replaced after any significant impact, as their energy-absorbing properties will be compromised. Zippers, waterproofing treatments, and other wear items also contribute to the total cost of ownership.

By breaking down the total cost over thousands of days of potential use, the value proposition becomes clear. A top-tier suit that costs $0.50 per day to own offers an immense return on investment if it prevents even a single serious injury. This analytical approach helps justify the higher initial outlay for gear with superior materials, construction, and protective features.

This table provides a sample calculation for the total cost of ownership of a high-end riding suit, demonstrating how a large initial investment breaks down into a manageable daily cost.

| Component | Expected Lifespan | Replacement Cost | Annual Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jacket/Pants Shell | 7 years | $700 | $100/year |

| CE Level 2 Armor Set | 5 years or after impact | $200 | $40/year |

| Zippers/Maintenance | 3-4 years | $100 | $30/year |

| Total Annual Cost | – | – | $170/year ($0.47/day) |

Key Takeaways

- Force Transmission is the Key Metric: A lower kN value means better protection, making CE-rated armor vastly superior to foam pads.

- System Integration Over Labels: Armor that doesn’t stay in place is useless. A secure fit is more critical than a Level 2 rating on a loose garment.

- Protection is a System: A complete setup includes impact absorption (armor), abrasion resistance (shell), and considers all impact zones (including hips).

The Layering System: How to Stay Warm at 40°F Without Bulky Electric Gear?

For a commuter, comfort is not just a luxury; it’s a safety factor. Being cold leads to distraction, fatigue, and reduced reaction time. While heated gear offers a powerful solution, it introduces complexity, wiring, and another system to manage. An effective, non-powered alternative is a modern layering system specifically adapted for the high-wind environment of motorcycling. The traditional three-layer hiking system (base, mid, shell) is often insufficient because it fails to account for the massive convective heat loss caused by wind blast.

The key to warmth on a motorcycle is trapping a layer of still air close to the body. Wind pressure at highway speeds can compress traditional insulation like down, eliminating its loft and thermal properties. The solution is a four-layer approach that incorporates a dedicated wind-blocking layer. This thin layer is worn between your insulating mid-layer (like fleece or synthetic fill) and your outer armored shell. Furthermore, the choice of insulation is critical. Modern synthetic insulations like Primaloft or 3M Thinsulate are engineered to retain their insulating properties even when compressed, making them far more effective for motorcycling than puffy materials.

Case Study: The Four-Layer System for Motorcycle Wind Protection

Analysis of thermal efficiency at speed shows that the standard three-layer hiking system is inadequate for motorcyclists due to extreme wind chill. A more effective strategy involves a fourth, dedicated wind-blocking layer positioned between the insulating mid-layer and the outer shell. This prevents wind from penetrating the insulation and carrying away body heat. Additionally, materials like Primaloft are superior to traditional down, as they maintain their thermal properties (loft) even when compressed by high-speed wind pressure, ensuring consistent warmth and comfort.

The next time you evaluate a piece of gear, look beyond the price tag and CE level. Apply this system-based approach to analyze its fit, coverage, and material science to build a truly protective and comfortable setup for your daily ride.